Mississippi River Mussels ( clams ) produce pearls.

Table of Contents

Excerpt from Discover!

America's Great River Road, by Pat Middleton, Volume 2 © 1992. May not be

reproduced without permission.

In 1884, a German by the name of J.F. Boepple founded the Mississippi

River pearl button industry by applying his native trade to the abundant Mississippi River

mussels. By 1890, Muscatine was known as the Pearl Button Capital of the World.

2,500 workers were employed in 43 different button-related businesses. In 1884, a German by the name of J.F. Boepple founded the Mississippi

River pearl button industry by applying his native trade to the abundant Mississippi River

mussels. By 1890, Muscatine was known as the Pearl Button Capital of the World.

2,500 workers were employed in 43 different button-related businesses.

Factories in

Muscatine received the rounded blanks cut from clam shells from as far away as Prairie du

Chien, Wisconsin, and Louisiana, Missouri. Round saws were used to cut blanks or circular

pieces from the clam shell. The white pearl shells were often 1/2 inch or more thick. This

blank was divided into several unfinished buttons which were ground on a traveling band

that passed under grindstones. A depression was made in each disk and holes drilled for

the thread. The buttons were then smoothed, polished with pumice stone and water in

revolving kegs, sorted, and sewed on cards. The "holey" shells and rough blanks

can still be found in the soil along the river. Factories in

Muscatine received the rounded blanks cut from clam shells from as far away as Prairie du

Chien, Wisconsin, and Louisiana, Missouri. Round saws were used to cut blanks or circular

pieces from the clam shell. The white pearl shells were often 1/2 inch or more thick. This

blank was divided into several unfinished buttons which were ground on a traveling band

that passed under grindstones. A depression was made in each disk and holes drilled for

the thread. The buttons were then smoothed, polished with pumice stone and water in

revolving kegs, sorted, and sewed on cards. The "holey" shells and rough blanks

can still be found in the soil along the river.

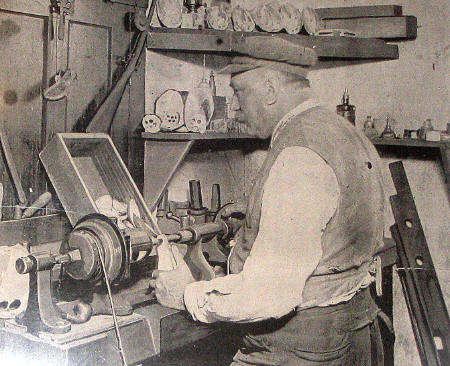

Much of the machinery used in the button industry was invented and

manufactured in Muscatine. An outstanding collection of memorabilia (including some of the

early button making equipment) is on display at the Laura Musser Home Museum. A new museum

devoted to the pearl button industry has recently opened.

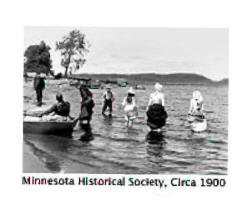

People did a lot of commercial clamming then in Lake Pepin and along

the river. Kettles dotted the shorelines where the clams were boiled to open the shells.

Empty shells were heaped along the shore.

My mother told me about

toe clamming in Stoddard. She would walk

along the shore in shallow water feeling for clams with her toes. She often showed me the

good pearl she had mounted on a ring. Buyers would visit the clammers to buy their harvest

of pearls, slugs, and "chicken feed."

Along the Mississippi

River. Mussels, clams produce river pearls

by Ruth Nissen of the Wisconsin DNR

Pearls have been a favorite gem since ancient times. Their appeal is

universal. Native Americans of the Upper Mississippi River Valley were wearing pearls in

necklaces and other ornaments when the early French explorers arrived. The pearls came

from freshwater mussels or clams found in the Mississippi and other rivers and streams.

They were most likely found while using the mussels for food and the shells for tempering

pottery.

Today, pearls are available in several types, natural or cultured and

freshwater or marine. Cultured pearls are created by inserting an irritant into the

shell of an oyster. The oyster then secretes a pearly coating to cover the irritant. A natural

pearl is pearl all the way through. A cultured pearl is mainly a mussel shell bead

with a very thin pearl coating.

Although most natural pearls are found in oysters, they also are found

in many different species of freshwater mussels or clams all over the world. Natural

pearls tend to be irregular in shape and not as desirable as the high-luster, spherical,

cultured pearls. However, the free sculpture of a misshapen freshwater pearl has an appeal

all its own.

Natural pearls come in a variety of colors. The tones of the freshwater

pearls are dictated by the mother shell. White is the most common, followed by pink. Other

colors depend on the type of mussels. Big washboard mussels usually have pink pearls, as

do the wartybacks. Threeridge mussels have pearls in shades of blue-green and lavendar.

Muckets produce fine pink pearls, and sand shells have salmon-pink pearls.

One pearl dealer in this area recalls a bright blue pearl that was found

about 15 years ago. Rumor says the finder bought a farm or ranch with the proceeds from

selling the pearl.

Shape of the Pearl

The shape of a pearl is determined by its location in a shell. Those

along the lip are round and are the most valuable. Wing-shaped pearls form along the back

of the shell, and irregular pearls form in the heels of shells.

Blister pearls, where the pearl is attached to the shell, are the most

common. Some people collect shells with blister pearls, and occasionally a free pearl

exists inside the blister pearl.

A good-sized irregular pearl can be found in about one in 100 clams.

However, a good-sized, natural, round pearl occurs only once in every 10,000 clams.

The future of the Mississippi River and its mussels is uncertain. Mussel

populations were impacted by their use in the button industry earlier in this century and

their use today in the cultured pearl industry. They also have been affected by changes in

the river brought on by the building of locks and dams, as well as pollution, siltation,

and navigational effects. (See Clam Lady of American Rivers)

Now the native species face a new threat, in the form of the invading zebra mussels.

(shown below)

The mussel, a simple creature with a unique ability to produce

magnificent pearls, has a colorful past and is an integral part of the fascinating history

of the river. Let us hope that native mussels never cease to be part of the river's

future.

Click here to find "anything Mississippi

River!

MISSISSIPPI RIVER HOME

| WATERWAY

CRUISE REPORTS

|

River Books, Note Cards and Gifts

| Feature

Articles | FISHING|

| Hand-painted

HISTORIC MAPS

| River

Classifieds

|

Contact Us | Press

Releases | Photo

Gallery | Links |BIRDING |

River Blog |

Please sign our Guestbook and request a FREE

miniguide to the Upper Mississippi River.

Web page design © 2011 by Great River

Publishing.

|

Factories in

Muscatine received the rounded blanks cut from clam shells from as far away as Prairie du

Chien, Wisconsin, and Louisiana, Missouri. Round saws were used to cut blanks or circular

pieces from the clam shell. The white pearl shells were often 1/2 inch or more thick. This

blank was divided into several unfinished buttons which were ground on a traveling band

that passed under grindstones. A depression was made in each disk and holes drilled for

the thread. The buttons were then smoothed, polished with pumice stone and water in

revolving kegs, sorted, and sewed on cards. The "holey" shells and rough blanks

can still be found in the soil along the river.

Factories in

Muscatine received the rounded blanks cut from clam shells from as far away as Prairie du

Chien, Wisconsin, and Louisiana, Missouri. Round saws were used to cut blanks or circular

pieces from the clam shell. The white pearl shells were often 1/2 inch or more thick. This

blank was divided into several unfinished buttons which were ground on a traveling band

that passed under grindstones. A depression was made in each disk and holes drilled for

the thread. The buttons were then smoothed, polished with pumice stone and water in

revolving kegs, sorted, and sewed on cards. The "holey" shells and rough blanks

can still be found in the soil along the river.