Table of

Contents

Marian Havlik's 10 grandchildren seldom

find grandma making chocolate chip cookies or teaching them how to knit.

Instead, they wend their way past stacks of specimen boxes, and scientific

reports for a lesson on the new computer.

Their grandma, known from St. Paul,

Minnesota, to Mobile, Alabama, simply as "that clam lady" is a kindly woman who

regularly directs divers in the murky river waters of the Midwest,

conducts mitigation projects and willingly goes nose-to-nose with such

heavy-weight bureaucracies as the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S.

Fish & Wildlife Service, and state departments of conservation, all in

defense of the living equivalent of a pet rock, the endangered Higgins Eye

Mussel.

Mobile, Alabama, simply as "that clam lady" is a kindly woman who

regularly directs divers in the murky river waters of the Midwest,

conducts mitigation projects and willingly goes nose-to-nose with such

heavy-weight bureaucracies as the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S.

Fish & Wildlife Service, and state departments of conservation, all in

defense of the living equivalent of a pet rock, the endangered Higgins Eye

Mussel.

Marian Havlik, an internationally known

expert on fresh-water mussels, came late to the world of

malacalogy

(the study of mollusks) when, in

1969, one of her five children decided to enter a science fair in 5th

grade. Her project was a study of ocean shells. The second year led mother

and daughter to explore the pearl button industry which nearly depleted

the freshwater mussels whose shells decorated the mud flats of the nearby

Mississippi River.

"When we began research for the science

fair that year," Havlik recalls, "we found an absolute dearth of

information for freshwater mussels of our own Mississippi River. I learned

that the large thick shells were used until the late 1930's to make pearl

buttons. But when we tried to learn about the pearl button industry or

even the pearls that are produced by freshwater mussels, we found nothing.

Nobody at area universities could help, nobody at the local National

Fishery Research Laboratory. I was amazed!"

Havlik and her daughter, Rosemarie,

chanced upon a clam buyer in Prairie du Chien, who eagerly shared the

knowledge he had accumulated from many years of commercial clamming ("musseling,"

in the southern states.") One of his contributions to the project included

a display of shells that he had collected and identified to the best of

his ability. One of those shells was later identified by Havlik as the

Higgins Eye, an historically rare species.

"The fourth year," Marian continues, "we

did another mussel project, this time with 100 live specimens. That was

the first time we set up aquariums in the house to study the mussels. I've

had them around ever since."

The clam buyer also gave Marian a 7

inch-wide, 2.2 pound Three-Ridged Mussel shell. The buyer's specimen was

60 years old, according to its growth rings. The most common size in the

river today is 3.5" and just a few ounces. What was happening to the

mussels? Why weren't they living as long as they used to? Very few clams

found today lived to be more than 20 or 25 years! She wrote various state

agencies, the DNR, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the state universities,

to suggest that studies be done and regulations put in place to protect

the defenseless bi-valves. She found that no one really knew anything

about the little critters. What was worse, nobody really cared to know

about them.

"A rare mussel is simply not as sexy as a

grizzly bear or bald eagle," Marian explains. "Yet the

clammer's

livelihood depended on having a

successfully reproducing population of mussels. I really felt

that some of these government

agencies were not doing as well by the clammers as they were by the deer

hunters, fishermen, and duck hunters. That bothered me. "

"So I started my own research program,

reading old books I found at the National Fishery Research Center; reading

observations and records made during the hey-day of the pearl button

industries."

A research trip to the University in

Winona, MN, brought her another "aha."

"Marian," the professor said, and she is

still grateful for his honest admission, "Marian, I cannot answer your

questions. You already know more than I do. "

"Well, that set me out on a whole new

quest. I visited museums of natural history throughout the country in

order to study their collections of freshwater mussels. I sat in on

planning meetings for the Great River Environmental Action Team and other

river commission meetings. I was the only woman at most of those

meetings."

"I knew I needed to get some formal

training in order to gain any credibility with the men in these agencies

and commissions. So in 1976 I applied to the Bush Leadership Foundation in

Minneapolis, Minnesota, for a grant to attend Ohio State University. There

I had 5 weeks of independent study with America's number one expert on

freshwater mussel species."

About this same time, the Higgins Eye was

considered for both federal and state endangered species lists. It

happened that the only recent proof of its continuing existence were the

specimens collected by the clam buyer in Prairie du Chien. Dr. Ruth Hine

of the Wisconsin DNR contacted Marian for her opinion as to the existence

of the mussel.

"I was now considered to be an expert,

but I didn't have it placed on the endangered species list," Marian

reminds me, "that process had already started. Shortly after, the Army

Corps of Engineers proceeded with dredging the East Channel at Prairie du

Chien even though I warned them that dredging would disrupt the best-known

habitat of the Higgins Eye, an endangered species. That's when I first

became known throughout the Corps of Engineers as "that clam lady."

"They dredged despite my warnings, and

afterward I found hundreds of Higgins Eye shells in the dredge spoil. I

wrote letters single-handedly to every federal agency I could think of,

every environmental club, senator, even President Carter, accusing the

Army Corps of disregarding the Endangered Species Act. All hell broke

loose and, after Congressional inquiries into the matter, the Army Corps

realized that never again could it dredge a channel without first doing a

survey of mussel species in the path of the dredge boat."

"As it happened, there was no one in the

Corps who could identify a mussel species. I became the person in the

right place, at the right time, with the right information."

"Sometimes I look back at the events of

the past twenty-five years and I wonder who planned it all; the

coincidences, the snowballing interest in freshwater mussels. Anyone who

takes up an environmental cause needs to realize that they must plan to

devote 20 or 25 years of their life to the effort. The bureaucracy moves

so slowly, but all it takes is one person who is willing to stick with the

battle. In the case of regulating mussels, I was that one person."

Today, Marian Havlik is active in many

environmental law issues, including mining and other environmental

legislation. Her company, Malacological Consultants, founded in 1977,

continues to do field surveys on heartland rivers: the Rock River in

Illinois, the Ohio River from Paducah to Cairo, the Meramec in Missouri

and the Elkhorn river in Nebraska. She is a pioneer in the new strategy of

mitigation, the process of moving mussel beds out of the way of

construction or dredging projects and reestablishing them among

communities in safer nearby locales.

"Many of our river systems are in such

bad shape," she cautions. "In 1994 we examined 130 sites on the Root River

in Minnesota and found shells from 15 mussel species. Only three species

had any live representatives. We found only five live mussels in two weeks

of study. Think of it! In 1977 we looked at

the Minnesota River near

Savage, MN. We found shells from 32 species and NOT ONE live specimen."

"What is killing the mussels? I agree

with studies showing that it is the cumulative result of barge traffic,

dredging, industrial pollution, erosion and agricultural impact.

Agriculture along streams and tributaries of the Mississippi and other

large rivers is having a devastating effect. Cows and horses degrade

stream and river banks. Pesticides, fertilizers, and sediments eventually

flow into the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers."

Marian notes finally that miners once

took canaries into the mines because they were very sensitive to changes

in oxygen. They provided an early warning that air quality was

deteriorating. The freshwater mussel serves the same purpose. The decline

in species diversity and numbers warns us of problems in our river

systems. Of 300 known mussel species in the U.S., 50 are endangered. Many

more are proposed for endangered status.

Zebra

Mussels

Threaten Native Mussels

(Photo, above) A colony of zebra mussels

has attached itself to the hard shell of a native mussel.

One great irony in Marian Havlik's life

is that having fought to protect mussels for 25 years, she now believes

their very

existence is threatened

by the fingernail-sized zebra mussel. This tiny striped mussel is native

to the Caspian Sea region of Asia and was introduced into American rivers

via the Great Lakes in 1991.

The zebra mussel builds huge colonies by

cementing itself onto any hard surfaceboat hulls, intake pipes, live wells

and most devastating, the shells of our native mussels. Colonies of 1500

zebra mussels have been found cemented to a single native mussel. The

shell becomes so encrusted the host can neither move nor filter feed and

dies.

"We will be lucky if any native mussels

can survive the influx for even five years," Havlik asserts. "The flood of

1993 flushed the Zebra Mussel throughout the length of the Mississippi

River and into its tributaries. They have spread far faster than we ever

dreamed possible."

Boaters and

divers are believed to be a primary transporter of zebra mussels to river

systems and land-locked lakes and quarries. Clean boats mean clean

waters...

What can

boaters do to discourage the

spread of zebra mussels and other exotic species?

Remove plants and animals from your boat,

trailer, accessory equipment before leaving access area. Put plants or

shells in trash can.

Drain and clean livewells, bilge water,

and transom wells before leaving access area. Empty water on land, not

into the water. Never dip bait buckets into one lake or river if it has

water from another in it.

Steam-clean or wash boats and trailers

with hot water (135-145 )when you have them home. Wash the bumpers, bait

buckets and any other hard surface that has been in the water. Flush hot

water through your motor's cooling system. Alternatively, use a salt

solution of 1/2 cup salt per gallon of water followed by a fresh water

flush. If possible, let everything dry for three days before transporting

your boat to another body of water. (Both hot water and drying will kill

the zebra mussel larvae.)

Footnote:

(Freshwater mussels are commonly referred to as "clams" on the Upper

Mississippi. "Clamming" is the

commercial collecting of

clams. Commonly referred to as "musseling" in the southern states.)

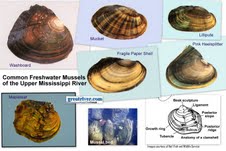

Most fresh water mussels in existence are

located in American rivers, very few species are found in European waters

Marian Havlik recently mailed in this update for boaters:

Pat:

Be sure to alert all of your readers of

the possibility of spreading Zebra Mussels when traveling around in

rivers. I strongly suggest that boaters never try to go from Lake Superior

thru the Brule River, and then portage to the St. Croix River (boundary

between part of Minnesota and Wisconsin). The National Park Service, the

Fish and Wildlife Service, and the MN and WI DNR's have been trying

desperately to keep the Zebra Mussel out of the St. Croix River because of

unique freshwater mussel populations. This is not a problem if trying to

access the Mississippi River from Lake Michigan through the Illinois

River.

Likewise, when these boaters are

returning home, or to rivers or lakes not infested with Zebra Mussels,

they should througly clean their boats with a bleach solution, or let them

dry out for at least a week or more if they have been in the Illinois,

Mississippi, Ohio, and other rivers known to be infested with the exotic

Zebra Mussel. Zebra Mussels can also cause problems with your boat motors

(clog up the water intake system) so keep your outboards tipped up when

not running your motor if you're going to be in infested waters for a

period of time.

Clean vegetation off of your boat and

trailer before traveling on highways (illegal in Minnesota to transport

exotic species in that state; Wisconsin is in the process of implementing

similar legislation).